Optics in Practice: An Expression Language AST

Part 3 of the Functional Optics for Modern Java series

In Part 1 and Part 2, we established why optics matter and how they work. Now it’s time to apply them to a real domain by building an expression language interpreter.

Expression languages are the backbone of modern Java infrastructure, from Spring Expression Language (SpEL) to rule engines like Drools. If you’ve ever configured a complex Spring application or written business rules, you’ve used one. In this article we will show how Java 25’s data-oriented programming features, combined with Higher-Kinded-J optics, make building such systems remarkably clean.

This is a domain where optics really shine.

Over the next three articles, we’ll build a complete expression language with parsing, type checking, optimisation, and interpretation. Along the way, you’ll see how optics transform what would otherwise be tedious tree manipulation into elegant, composable operations.

Running the Examples

Article Code

All code examples from this article have runnable demos:

- ExprDemo: Building ASTs, using prisms, and Focus DSL composition

- OptimiserDemo: Constant folding, identity simplification, and complex optimisation

The AST types are defined in org.higherkindedj.article3.ast, with transformations in org.higherkindedj.article3.transform.

The Expression Language Domain

What exactly are we building? A small but powerful expression language suitable for:

- Configuration expressions:

if (env == "prod") then timeout * 2 else timeout - Rule engines:

price > 100 && customer.tier == "gold" - Template systems:

"Hello, " + user.name + "!" - Domain-specific calculations:

principal * (1 + rate) ^ years

The language will support:

- Literal values (integers, booleans, strings)

- Variables with lexical scoping

- Binary operations (arithmetic, comparison, logical)

- Conditional expressions (if-then-else)

Our design goals are:

- Type-safe: The compiler catches structural errors

- Immutable: Expressions never change; transformations produce new trees

- Transformable: Easy to analyse, optimise, and rewrite

This third goal is where optics become essential. An expression tree is a recursive structure where any node might contain arbitrarily nested sub-expressions. Transforming such trees manually (with pattern matching and reconstruction) quickly becomes unwieldy. Optics provide a disciplined approach.

Building on Data-Oriented Foundations

Part 1 introduced Java 25’s data-oriented programming features. As Brian Goetz articulates in Data-Oriented Programming in Java, the core insight is that “data is just data”: immutable, transparent, and separate from behaviour. Records, sealed interfaces, and pattern matching embody this philosophy beautifully.

Eric Normand’s work on data-oriented programming (from the Clojure tradition) takes this further: behaviour should be implemented as pure functions over immutable data, with polymorphism achieved through pattern matching rather than method dispatch. Java 25 now supports this style naturally.

Yet there’s a tension that pure DOP does not fully address. When behaviour is separate from data, where do structural operations live? Functions that transform nested trees must understand the shape of every node. In Normand’s terms, we’ve separated “what the data is” from “what we do with it”, but tree transformations blur this boundary: they’re operations intimately tied to structure.

This is precisely where optics prove their worth. They’re not behaviour embedded in data (that would violate DOP principles). They’re reified access paths; first-class values representing the structure of your types. The structure of a record implies its lenses; the variants of a sealed interface imply its prisms. Optics make this correspondence explicit and composable.

A Map Analogy: Optics as Directions

Think of optics like directions in a treasure map. The treasure (This is your data) doesn’t know the directions to itself; it just is. But the directions (The optics) are separate, shareable instructions that anyone can follow.

A lens is like directions to a specific room in a house: “Go to the kitchen.” You’ll always find the kitchen there. A prism is like directions that might not apply: “If there’s a garden, go to the fountain.” Some houses have gardens; some don’t. A traversal is like directions to multiple destinations: “Visit every bedroom.”

The power comes from composition. “Go to the garden, then to the fountain, then to the bench” chains directions together. If any step fails (no garden?), you stop gracefully. Optics compose the same way: each step may narrow, widen, or multiply your focus, and the types track this automatically.

Designing the AST

An Abstract Syntax Tree (AST) represents the structure of code as a tree of nodes. Each node type corresponds to a language construct.

Start Simple

We’ll begin with a minimal four-variant AST:

public sealed interface Expr {

record Literal(Object value) implements Expr {}

record Variable(String name) implements Expr {}

record Binary(Expr left, BinaryOp op, Expr right) implements Expr {}

record Conditional(Expr cond, Expr thenBranch, Expr elseBranch) implements Expr {}

}

public enum BinaryOp {

ADD, SUB, MUL, DIV, // Arithmetic

EQ, NE, LT, LE, GT, GE, // Comparison

AND, OR // Logical

}

This covers more than you might expect:

Literal(42): integer constantLiteral(true): boolean constantVariable("x"): variable referenceBinary(Variable("a"), ADD, Literal(1)):a + 1Conditional(Variable("flag"), Literal(1), Literal(0)):if flag then 1 else 0

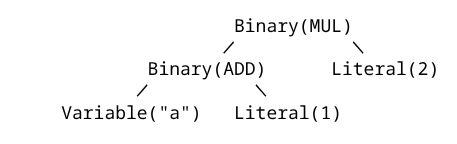

Here’s how (a + 1) * 2 looks as an AST:

The recursive nature is already apparent: Binary contains two Expr children, and Conditional contains three. Any transformation must handle this recursion.

Why Sealed Interfaces?

The sealed keyword is Java’s answer to sum types: a closed set of variants that the compiler understands completely. When we write a switch over Expr, Java 25 guarantees exhaustiveness:

String describe(Expr expr) {

return switch (expr) {

case Literal(var v) -> "Literal: " + v;

case Variable(var n) -> "Variable: " + n;

case Binary(var l, var op, var r) -> "Binary: " + op;

case Conditional(_, _, _) -> "Conditional";

}; // No default needed; compiler knows this is exhaustive

}

Notice the unnamed pattern _ for components we don’t need, a Java 22+ feature that reduces noise. If we later add a new variant like FunctionCall, the compiler flags every incomplete switch. This compile-time safety is essential for language implementations where missing a case means silent bugs.

Why Records?

Records give us:

- Immutability by default

- Automatic

equals(),hashCode(),toString() - Pattern matching with deconstruction

- A natural fit for optics (each component becomes a lens target)

The combination of sealed interfaces and records creates what functional programmers call an algebraic data type (ADT): a sum of products that’s both type-safe and pattern-matchable.

The Visitor Pattern: A DOP Perspective

The traditional Visitor pattern embeds traversal logic into your data types via accept() methods. This violates a core DOP principle: data should be transparent and behaviour-free. As Goetz notes, the Visitor pattern exists largely because Java lacked pattern matching; it’s a workaround, not a solution.

With sealed interfaces and pattern matching, we can write operations as standalone functions:

Expr foldConstants(Expr expr) {

return switch (expr) {

case Binary(Literal(var l), var op, Literal(var r)) ->

evaluate(l, op, r).map(Literal::new).orElse(expr);

case Binary(var l, var op, var r) ->

new Binary(foldConstants(l), op, foldConstants(r));

case Conditional(var c, var t, var e) ->

new Conditional(foldConstants(c), foldConstants(t), foldConstants(e));

case Literal _, Variable _ -> expr;

};

}

No interfaces to implement, no accept() methods polluting our data types, and the compiler verifies exhaustiveness. This is DOP in action: pure data, external functions, pattern-matched polymorphism.

Yet notice the manual reconstruction in the Binary and Conditional cases. This recursive boilerplate appears in every tree transformation. DOP gives us improved reading; the reconstruction cascade remains.

Generating Optics for the AST

This reconstruction problem is precisely what optics solve. With three annotations, Higher-Kinded-J generates a complete toolkit for navigating and transforming our AST:

@GeneratePrisms // Generates prisms for each sealed variant

public sealed interface Expr {

@GenerateLenses @GenerateFocus

record Literal(Object value) implements Expr {}

@GenerateLenses @GenerateFocus

record Variable(String name) implements Expr {}

@GenerateLenses @GenerateFocus

record Binary(Expr left, BinaryOp op, Expr right) implements Expr {}

@GenerateLenses @GenerateFocus

record Conditional(Expr cond, Expr thenBranch, Expr elseBranch) implements Expr {}

}

At compile time, Higher-Kinded-J’s annotation processor generates:

Prisms for Each Variant

// Generated: ExprPrisms.java

public final class ExprPrisms {

public static Prism<Expr, Literal> literal() { ... }

public static Prism<Expr, Variable> variable() { ... }

public static Prism<Expr, Binary> binary() { ... }

public static Prism<Expr, Conditional> conditional() { ... }

}

Each prism lets us:

- Check if an

Expris a specific variant - Extract the variant if it matches

- Transform just that variant, leaving others unchanged

Lenses for Each Field

// Generated: LiteralLenses.java

public final class LiteralLenses {

public static Lens<Literal, Object> value() { ... }

}

// Generated: BinaryLenses.java

public final class BinaryLenses {

public static Lens<Binary, Expr> left() { ... }

public static Lens<Binary, BinaryOp> op() { ... }

public static Lens<Binary, Expr> right() { ... }

}

Each lens lets us:

- Get a field from a node

- Set a field, producing a new node

- Modify a field with a function

Focus DSL: Fluent Navigation

The @GenerateFocus(generateNavigators = true) annotation generates Focus classes with fluent navigation:

// Generated: BinaryFocus.java

public final class BinaryFocus {

public static FocusPath<Binary, Expr> left() { ... }

public static FocusPath<Binary, BinaryOp> op() { ... }

public static FocusPath<Binary, Expr> right() { ... }

}

Focus classes wrap lenses in FocusPath objects that enable method chaining without explicit composition. The difference becomes clear when you navigate nested structures.

Composition: Where Optics Earn Their Keep

The benefit comes when we compose these optics. Here’s the traditional approach with raw optics:

// Raw optics: explicit composition with andThen

Affine<Binary, Object> leftLiteralValue =

BinaryLenses.left()

.andThen(ExprPrisms.literal())

.andThen(LiteralLenses.value());

Binary expr = new Binary(new Literal(5), ADD, new Variable("x"));

Optional<Object> value = leftLiteralValue.getOptional(expr);

// Optional[5]

With the Focus DSL, this becomes fluent navigation:

// Focus DSL: fluent method chaining

Binary expr = new Binary(new Literal(5), ADD, new Variable("x"));

Optional<Object> value = BinaryFocus.left()

.via(ExprPrisms.literal())

.via(LiteralLenses.value())

.getOptional(expr);

// Optional[5]

Both approaches navigate from Binary → left (Expr) → as Literal → value, but the Focus DSL reads more naturally. As we add navigators in Part 4, this becomes even more readable.

Why Optics Instead of Just Pattern Matching?

You might wonder: “Java 25’s pattern matching is already elegant; why add another abstraction?”

Three compelling reasons:

1. Composition Across Depth

Pattern matching handles one level at a time. To reach a deeply nested value, you nest matches:

// Pattern matching: explicit nesting

if (expr instanceof Binary(Binary(var ll, _, _), _, _)) {

// Access left-of-left

}

Optics compose to arbitrary depth. With the Focus DSL, it reads naturally:

// Focus DSL: fluent path

AffinePath<Expr, Expr> leftOfLeft = ExprPrisms.binary()

.via(BinaryFocus.left())

.via(ExprPrisms.binary())

.via(BinaryFocus.left());

// Or with navigators (preview of Article 4):

// BinaryFocus.left().asBinary().left()

2. Bidirectional Access

Pattern matching reads data. Optics read and write:

// With Focus DSL paths:

FocusPath<Binary, Expr> leftPath = BinaryFocus.left();

// Read the left operand

Expr left = leftPath.get(binaryExpr);

// Replace the left operand (returns new immutable tree)

Binary updated = leftPath.set(newLeft, binaryExpr);

// Transform the left operand

Binary transformed = leftPath.modify(this::optimize, binaryExpr);

The modify operation is particularly powerful: it extracts, transforms, and rebuilds in one step, handling all the immutable reconstruction automatically. The Focus DSL makes this read naturally.

3. Reusable Paths

A pattern match is code you write inline. An optic is a value you can store, pass, and reuse:

// Define once using Focus DSL

private static final FocusPath<Binary, Expr> leftOperand = BinaryFocus.left();

// Use anywhere

Binary opt1 = leftOperand.modify(this::fold, expr1);

Binary opt2 = leftOperand.modify(this::fold, expr2);

Focus paths are first-class values. Store them in fields, pass them to methods, compose them dynamically. This becomes invaluable when the same navigation pattern appears across multiple transformations.

Basic Transformations

Let’s implement some fundamental AST transformations using optics.

Transforming Literals

Suppose we want to increment all integer literals by one:

public static Expr incrementLiterals(Expr expr) {

Prism<Expr, Literal> literalPrism = ExprPrisms.literal();

return literalPrism.modify(lit -> {

if (lit.value() instanceof Integer i) {

return new Literal(i + 1);

}

return lit;

}, expr);

}

There is a problem here. This only transforms the top-level expression. If the literal is nested inside a Binary, it won’t be touched. We need recursion.

The Recursive Challenge

Here’s the manual approach to transforming all literals in a tree:

public static Expr incrementAllLiterals(Expr expr) {

return switch (expr) {

case Literal(var v) ->

v instanceof Integer i ? new Literal(i + 1) : expr;

case Variable(_) -> expr;

case Binary(var l, var op, var r) ->

new Binary(incrementAllLiterals(l), op, incrementAllLiterals(r));

case Conditional(var c, var t, var e) ->

new Conditional(

incrementAllLiterals(c),

incrementAllLiterals(t),

incrementAllLiterals(e));

};

}

This works, but it’s very tedious. Every transformation requires the same recursive boilerplate code. We’re manually threading the transformation through every node type.

A Reusable Transformation Pattern

We can extract the recursion into a reusable function:

public static Expr transformExpr(Expr expr, Function<Expr, Expr> transform) {

// First, recursively transform children

Expr transformed = switch (expr) {

case Literal(_), Variable(_) -> expr;

case Binary(var l, var op, var r) ->

new Binary(transformExpr(l, transform), op, transformExpr(r, transform));

case Conditional(var c, var t, var e) ->

new Conditional(

transformExpr(c, transform),

transformExpr(t, transform),

transformExpr(e, transform));

};

// Then apply the transformation to this node

return transform.apply(transformed);

}

Now our increment becomes:

Expr result = transformExpr(expr, e ->

ExprPrisms.literal().modify(lit ->

lit.value() instanceof Integer i ? new Literal(i + 1) : lit,

e));

In Part 4, we’ll see how traversals improve this further. For now, let’s work with what we have.

Working with the Sum Type

Prisms shine when working with the variants of our sealed interface.

Safe Type Checking

Traditional instanceof checks are verbose and error-prone:

if (expr instanceof Binary binary) {

if (binary.left() instanceof Literal leftLit) {

// do something with leftLit

}

}

With the Focus DSL, we compose the checks fluently:

// Compose prism and lens with andThen(), yielding an Affine

// Then wrap in AffinePath for fluent operations

AffinePath<Expr, Object> leftLiteralValue =

AffinePath.of(

ExprPrisms.binary()

.andThen(BinaryLenses.left())

.andThen(ExprPrisms.literal())

.andThen(LiteralLenses.value()));

Optional<Object> value = leftLiteralValue.getOptional(expr);

The composed path handles all the type checking internally. If expr isn’t a Binary, or if its left operand isn’t a Literal, the result is Optional.empty().

Conditional Transformation

Prisms let us transform specific variants while leaving others unchanged:

// Double all integer literals, leave everything else alone

Expr doubled = ExprPrisms.literal().modify(lit -> {

if (lit.value() instanceof Integer i) {

return new Literal(i * 2);

}

return lit;

}, expr);

If expr isn’t a Literal, it’s returned unchanged. No explicit instanceof check is needed.

Pattern-Based Matching

We can combine pattern matching with optics for complex structural tests:

// Match: Binary with ADD operator and Literal(0) on the right

// This is the pattern for "x + 0" which we can simplify to "x"

public static Optional<Expr> matchAddZero(Expr expr) {

return switch (expr) {

case Binary(var left, BinaryOp.ADD, Literal(Integer v)) when v == 0 ->

Optional.of(left);

default -> Optional.empty();

};

}

This pattern matching is where Java’s native features work well alongside optics. Use pattern matching for complex structural tests; use optics for transformations and deep access.

Building a Simple Optimiser

Let’s put everything together to build a constant folder; an optimiser that evaluates constant expressions at compile time.

Constant Folding

Here is the idea. If both operands of a binary expression are literals, we can compute the result:

public static Expr foldConstants(Expr expr) {

return transformExpr(expr, ExprOptimiser::foldBinary);

}

private static Expr foldBinary(Expr expr) {

// Java 25: Switch with nested record patterns

return switch (expr) {

case Binary(Literal(Object lv), BinaryOp op, Literal(Object rv)) -> {

Object result = evaluate(lv, op, rv);

yield result != null ? new Literal(result) : expr;

}

default -> expr;

};

}

private static Object evaluate(Object left, BinaryOp op, Object right) {

return switch (left) {

case Integer l when right instanceof Integer r -> switch (op) {

case ADD -> l + r;

case SUB -> l - r;

case MUL -> l * r;

case DIV -> r != 0 ? l / r : null;

case EQ -> l.equals(r);

case NE -> !l.equals(r);

case LT -> l < r;

case LE -> l <= r;

case GT -> l > r;

case GE -> l >= r;

default -> null;

};

case Boolean l when right instanceof Boolean r -> switch (op) {

case AND -> l && r;

case OR -> l || r;

case EQ -> l.equals(r);

case NE -> !l.equals(r);

default -> null;

};

default -> null;

};

}

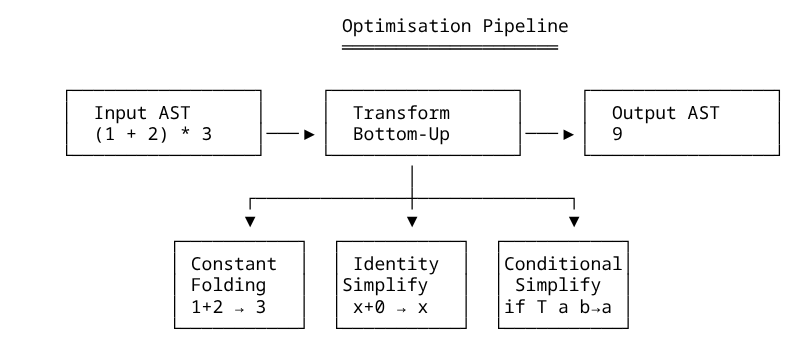

Example: Folding (1 + 2) * 3

Expr expr = new Binary(

new Binary(new Literal(1), ADD, new Literal(2)),

MUL,

new Literal(3)

);

System.out.println("Before: " + format(expr));

// Before: ((1 + 2) * 3)

Expr optimised = foldConstants(expr);

System.out.println("After: " + format(optimised));

// After: 9

The optimiser transforms ((1 + 2) * 3) to 9 in a single pass. The inner 1 + 2 is folded to 3, then 3 * 3 is folded to 9.

Identity Simplification

We can add more optimisations using Java 25’s enhanced pattern matching with guards:

private static Expr simplifyIdentities(Expr expr) {

return switch (expr) {

// x + 0 = x, x * 1 = x

case Binary(var left, BinaryOp.ADD, Literal(Integer v)) when v == 0 -> left;

case Binary(var left, BinaryOp.MUL, Literal(Integer v)) when v == 1 -> left;

// x * 0 = 0

case Binary(_, BinaryOp.MUL, Literal(Integer v)) when v == 0 -> new Literal(0);

// 0 + x = x, 1 * x = x

case Binary(Literal(Integer v), BinaryOp.ADD, var right) when v == 0 -> right;

case Binary(Literal(Integer v), BinaryOp.MUL, var right) when v == 1 -> right;

// 0 * x = 0

case Binary(Literal(Integer v), BinaryOp.MUL, _) when v == 0 -> new Literal(0);

default -> expr;

};

}

Composing Optimisations

Multiple optimisation passes compose quite naturally:

public static Expr optimise(Expr expr) {

Expr result = expr;

Expr previous;

// Run until fixed point (no more changes)

do {

previous = result;

result = transformExpr(result, e ->

simplifyIdentities(foldBinary(e)));

} while (!result.equals(previous));

return result;

}

This runs both optimisations repeatedly until the expression stops changing. The immutability of our AST makes equality checking trivial; we can use equals() directly.

Summary

We’ve built a solid foundation for expression language development using Java 25’s data-oriented programming features:

- Sealed interfaces define a closed universe of expression types

- Records provide immutable, transparent data carriers

- Pattern matching enables clean, exhaustive case analysis

- Optics (via Higher-Kinded-J) add composable, bidirectional transformations

- Focus DSL makes optic composition fluent and readable

Optics and the DOP Philosophy

There’s a deeper point here worth pausing on. Critics of pure data-oriented programming sometimes observe that while DOP excels at describing data, it offers less guidance on transforming it. Pattern matching destructures beautifully but reconstructs tediously. The purity of “data separate from behaviour” runs into friction when behaviour must intimately understand data’s shape.

Optics resolve this tension deftly. They’re not methods on your data types (that would embed behaviour). They’re not external functions that pattern-match (that leads to reconstruction cascades). They’re something new: structural correspondences reified as values.

The @GenerateLenses and @GeneratePrisms annotations embody this insight. The structure of a record implies its lenses; the variants of a sealed interface imply its prisms. Higher-Kinded-J makes these implications explicit and composable. You’re not adding behaviour to data; you’re deriving navigation from structure.

This is why optics feel natural alongside DOP rather than against it. Both emphasise that structure should be transparent and operations should compose. Optics simply extends these principles from reading to writing.

What’s Next

There’s a limitation in our current approach: the transformExpr function is hand-written boilerplate. Every time we add a new expression type, we must update it. This violates the DRY principle and risks bugs when someone forgets.

In Part 4, we’ll introduce traversals and the Focus DSL’s TraversalPath: optics that focus on multiple values simultaneously. This is where the Focus DSL becomes powerful:

// Preview: what's coming in Part 4

TraversalPath<Company, Employee> allEmployees = CompanyFocus

.departments()

.each() // Navigate into each department

.employees()

.each(); // Navigate into each employee

// Modify all employees in one expression

Company updated = allEmployees.modifyAll(Employee::promote, company);

With the Focus DSL’s collection navigation (each(), at(), atKey()), we can:

- Eliminate manual recursion:

TraversalPath.each()replaces switch-based boilerplate - Collect values fluently:

allEmployees.getAll(company)returns all focused values - Chain arbitrarily deep: Navigate through nested collections with method chains

- Apply conditional updates:

modifyWhen()transforms only elements matching a predicate

We’ll also tackle dead code elimination and common subexpression elimination, demonstrating how the Focus DSL scales to real compiler optimisations.

Further Reading

Algebraic Data Types in Java

-

Brian Goetz, “Towards Better Serialization”: Explores how records and sealed types create ADTs, with implications for pattern matching.

-

Scott Logic, “Algebraic Data Types and Pattern Matching with Java”: A thorough introduction to product types, sum types, and pattern matching in modern Java. Demonstrates how sealed interfaces and records implement ADTs with compile-time safety guarantees.

Expression Languages and AST Design

-

Terence Parr, Language Implementation Patterns (Pragmatic Bookshelf, 2010): The definitive guide to building interpreters and compilers, covering AST design patterns we use here.

-

Robert Nystrom, Crafting Interpreters: A freely available, nicely written guide to interpreter construction. The “tree-walk interpreter” chapters parallel our approach.

DOP and the Expression Problem

-

Philip Wadler, “The Expression Problem” (1998): The classic formulation of the tension between adding new data types versus new operations. DOP with optics offers one resolution.

-

The expression problem asks: can you add both new variants and new operations without modifying existing code? Sealed interfaces make adding operations easy (write a function); optics make the operations themselves composable and reusable.

Higher-Kinded-J

-

Prism Documentation: API reference for working with sum types.

-

Focus DSL Guide: Fluent navigation with FocusPath, AffinePath, and TraversalPath.

-

Effect Path API Guide: Railway-style error handling with MaybePath, EitherPath, and ValidationPath.

Next time

Next time in Part 4 we look at how we visit all nodes in the tree, not just the top level. This is where traversals become essential. A traversal focuses on zero or more elements within a structure, making it perfect for recursive tree operations.