This is the sixth post in a series exploring types and type systems. Other posts have looked at

- Algebraic Data Types with Java

- Variance, Phantom and Existential types in Java and Scala

- Intersection and Union Types with Java and Scala

- Functors and Monads with Java and Scala

- Higher Kinded Types with Java and Scala

What is Recursion?

In simple terms, recursion is a process where a function calls itself directly or indirectly in order to solve a problem. The process involves breaking down a complex problem into smaller sub-problems. Each function call works on a smaller problem subset until finally a terminating case is reached. Think of it like a set of Matryoshka (Russian) stacking dolls, where each doll contains a slightly smaller version of itself until we reach the smallest doll.

Recursion is one of those concepts that can feel beautifully elegant when solving certain problems (think tree traversals, mathematical sequences), but as we will see next it comes with a potential dreaded problem: the StackOverflowError.

Calculating Factorials

Calculating factorials is a classic example of recursion. Factorial is recursive because the factorial of a number n can be defined in terms of the factorial of a smaller number, n-1. This self-referential nature allows for a natural implementation of the factorial function using recursion, where the function calls itself to calculate the factorial of progressively smaller numbers until it reaches a base case (n=1 or n=0).

import java.math.BigInteger;

class Calculator {

// Calculate the factorial n! (n * (n-1) * ... * 1)

static BigInteger factorial(BigInteger n) {

// Base case: Stop condition for the recursion

if (n.compareTo(BigInteger.ZERO) < 0) {

throw new IllegalArgumentException("Factorial not defined for negative numbers");

}

if (n.equals(BigInteger.ZERO) || n.equals(BigInteger.ONE)) {

return BigInteger.ONE;

}

// Recursive step: Call itself with a smaller problem (n-1)

// Note: Multiplication happens *after* the recursive call returns.

return n.multiply(factorial(n.subtract(BigInteger.ONE)));

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

System.out.println("5! = " + factorial(BigInteger.valueOf(5))); // Output: 5! = 120

System.out.println("Calculating factorial for a large number...");

System.out.println("20000! = " + factorial(BigInteger.valueOf(30000)));

// Exception in thread "main" java.lang.StackOverflowError

}

}

Looks clean, and for small numbers it works perfectly, but for larger values problems start to manifest.

The Call Stack and StackOverflowError

Every time we call a method in Java (recursive or not), the JVM pushes a “stack frame” onto the call stack. This frame holds information about the method call:

- Local Variables: The variables declared inside the method(e.g

nin thefactorialmethod). - Parameters: Where execution should resume in the

callingmethod afterthismethod completes.

After a method completes then the stack frame is popped off the stack.

Understanding the Call Stack

Let’s look at the call stack for factorial(5)

| Call | Returns | Frame |

|---|---|---|

| main calls factorial(5) | Frame for factorial(5) pushed | |

| factorial(5) calls factorial(4) | Frame for factorial(4) pushed on top | |

| factorial(4) calls factorial(3) | Frame for factorial(3) pushed on top | |

| factorial(3) calls factorial(2) | Frame for factorial(2) pushed on top | |

| factorial(2) calls factorial(1) | Frame for factorial(1) pushed on top | |

| factorial(1) hits the base case | returns 1 | Frame is popped |

| factorial(2) calculates 2 * 1 | returns 2 | Frame is popped |

| factorial(3) calculates 3 * 2 | returns 6 | Frame is popped |

| factorial(4) calculates 4 * 6 | returns 24 | Frame is popped |

| factorial(5) calculates 5 * 24 | returns 120 | Frame is popped |

Each thread in Java is allocated a stack. Once the method completes execution, its stack frame is popped off the stack. The total stack size allocated to each thread determines the amount of data its call stack can hold. The default stack size varies by JVM implementation, but it’s typically around 1MB for a standard JVM.

If we try to calculate a large factorial we need to hold a lot of frames. Each frame contains local variables, operand

stack, and frame data. Once the memory requirement of all the stack frames held exceeds the stack memory available then

we get a StackOverFlowError.

This is the primary problem with deep recursion in standard Java: it consumes stack memory proportional to the depth of the recursion.

Tail Recursion

There’s a specific type of recursion called tail recursion. A method call is in “tail position” if it’s the absolute last thing the method does before returning. The result of the recursive call is directly returned, without any further computation.

We can rewrite factorial using a helper method to be tail recursive, typically by using an “accumulator”

import java.math.BigInteger;

class Calculator2 {

// Using BigInteger to support large factorial results

static BigInteger factorial(BigInteger n) {

if (n.compareTo(BigInteger.ZERO) < 0) {

throw new IllegalArgumentException("Factorial not defined for negative numbers");

}

// Start the helper with the initial accumulator value (1)

return factorialHelper(n, BigInteger.ONE);

}

// Tail-recursive helper method

static BigInteger factorialHelper(BigInteger n, BigInteger accumulator) {

// Base case: return the final accumulated result

if (n.equals(BigInteger.ZERO) || n.equals(BigInteger.ONE)) {

return accumulator;

}

// Recursive step: The call is the VERY LAST action.

// The multiplication happens *before* the recursive call.

return factorialHelper(n.subtract(BigInteger.ONE), accumulator.multiply(n)); // TAIL RECURSIVE call

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

System.out.println("5! = " + factorial(BigInteger.valueOf(5))); // Output: 5! = 120

System.out.println("Calculating factorial for a large number...");

System.out.println("20000! = " + factorial(BigInteger.valueOf(20000)));

// Exception in thread "main" java.lang.StackOverflowError

}

}

Even though this is tail recursive, it still fails in Java with a StackOverflowError.

Unlike Java many programming languages - especially functional ones like Scala and Haskell - perform a process known as Tail Call Optimisation (TCO). When the compiler sees a tail recursive call, it understands that it does not need to keep the current stack frame for the next call.

This effectively turns the recursion into iteration. With TCO, tail recursive functions can run indefinitely without

continuously consuming stack space.

The standard JVM does not implement TCO

How does Scala achieve TCO?

Instead of relying on the JVM, Scala implements Tail Call Optimisation at the compile time. Here’s the breakdown:

- Detection: The Scala compiler (

scalac) analyses the code to detect methods that make recursive calls to themselves in tail position. Remember, a tail position call is the absolute last action performed by the method before it returns. - Transform into Iteration: Once the compiler has identified a self-recursive tail call, it rewrites the recursive method into an iterative one in the generated JVM bytecode.

- Updates to the method’s parameters (as if they were local variables).

- A jump (like a goto in bytecode terms) back to the beginning of the method’s logic. This effectively creates a while loop structure within the bytecode.

- Reuse Stack Frame: By replacing the recursive call with parameter updates and a jump within the same method, no new stack frame is pushed onto the call stack for the “recursive” step. The method re-runs its logic with new values within the existing stack frame.

- The

@tailrecannotation: Including the annotation tells the compiler to attempt to optimise the method for TCO. If it then fails because the method annotated is not direct self-recursion or in the tail position then it will raise an error to inform us that the method is not safe from overflow.

import scala.annotation.tailrec

object Factorial {

def calculate(n: Int): BigInt = {

// Helper function annotated for guaranteed TCO

@tailrec

def factorialHelper(x: Int, accumulator: BigInt): BigInt = {

if (x <= 1) {

accumulator // Base case: return accumulator

} else {

// Tail Position: The recursive call is the last action.

// Parameter 'x' becomes 'x - 1' for the next iteration.

// Parameter 'accumulator' becomes 'accumulator * x' for the next iteration.

factorialHelper(x - 1, accumulator * x)

}

}

if (n < 0) throw new IllegalArgumentException("Negative number")

factorialHelper(n, BigInt(1)) // Initial call to the helper

}

@main

def main(): Unit = {

println(s"5! = ${calculate(5)}")

// This will run without StackOverflowError, even for large numbers

// (though BigInt might consume heap memory)

try {

println(s"Calculating 20000!...")

val largeFactorial = calculate(20000)

println("Calculation finished successfully!")

// println(largeFactorial) // Might be too large to print meaningfully

} catch {

case e: StackOverflowError => println(s"Unexpected StackOverflowError: $e") // Should not happen

case e: Throwable => println(s"An error occurred: $e")

}

}

}

The Scala compiler recognises the @tailrec annotation and the recursive call factorialHelper(x - 1, accumulator * x) in

tail position. It effectively rewrites the bytecode to behave in an iterative loop.

What is a Thunk

A thunk is simply a way to wrap up a piece of computation so you can execute it later. We can think of it as a way

of putting a task in a container to be opened and performed only when needed.

In Java this is a familiar concept that we see with Supplier<T>, Runnable and Lambdas.

java.util.function.Supplier<T>: This is perhaps the closest standard Java interface to a thunk that produces a

value. A Supplier<T> has a single method: T get().

- It takes no arguments and represents a way to supply a value

T. - The computation in the

get()method doesn’t happen until get() is actually called.

// 1. Define a Thunk as a Supplier using a lambda expression.

// This supplier takes no arguments () and returns a LocalDateTime.

Supplier<LocalDateTime> currentTimeSupplier = () -> LocalDateTime.now();

// 2. Use the supplier to get a value.

// Calling .get() executes the lambda expression.

LocalDateTime time1 = currentTimeSupplier.get();

// Format the time for printing

DateTimeFormatter formatter = DateTimeFormatter.ofPattern("yyyy-MM-dd HH:mm:ss.SSS");

System.out.println("Time supplied (call 1): " + time1.format(formatter));

// Let's wait a bit and call it again to show it generates a new value

try {

Thread.sleep(500); // Pause for 500 milliseconds

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

Thread.currentThread().interrupt();

}

// 3. Call .get() again - it re-executes the lambda, supplying the *current* time now.

LocalDateTime time2 = currentTimeSupplier.get();

System.out.println("Time supplied (call 2): " + time2.format(formatter));

In this example, currentTimeSupplier is essentially a thunk. It’s an object (a Supplier instance, created via a lambda)

that encapsulates the potential computation of currentTimeSupplier. The computation is deferred until get() is invoked.

java.lang.Runnable: This is like a thunk for an action that doesn’t return a value (void). It has a run() method that takes no arguments.

You often use Runnable with Threads or Executors to define a task to be executed later or concurrently.

Runnable actionThunk = () -> System.out.println("Performing action later!");

// The message isn't printed yet.

// Execute the action later:

System.out.println("About to execute action thunk...");

actionThunk.run(); // Action happens now.

Why use Thunks

Thunks are fundamental building blocks for several powerful techniques:

- Lazy Evaluation: We already saw with the

Supplierthat we can avoid computing something (potentially expensive) unless we actually need the result. This improves performance by avoiding unnecessary work. The logic that performs the initialisation on first access is behaving like a thunk. - Concurrency: Using

Runnable, you package the work into a thunk and hand it off to another thread or anExecutorServicefor asynchronous execution. - Memoization: You can easily build a “memoized” thunk that executes the computation only the first time it’s needed, caches the result, and returns the cached result on subsequent calls.

- Managing Control Flow: Thunks can be used to implement complex control structures. One such structure that we will look at next is trampolining that uses thunks to turn deep recursion into iteration.

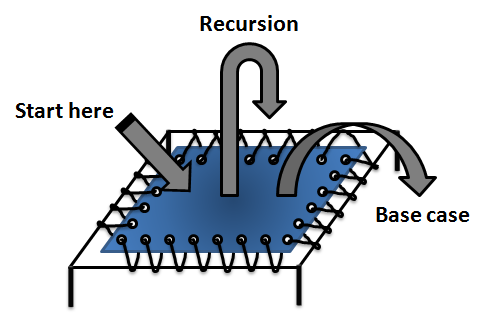

Trampoline to the rescue

Imagine instead of climbing a huge staircase (deepening the call stack), you’re bouncing on a trampoline. You always return to the trampoline’s surface (a central control loop) before taking the next bounce (the next computation step)

The Trampoline pattern is designed to execute deeply recursive (especially tail-recursive) computations without blowing the stack. It does this by replacing direct recursive calls with returning an object representing the next computation step. A controlling loop then executes these steps iteratively.

We need a way to represent two states: either the computation is finished (Done) or there’s more work to do (More). A sealed interface is perfect for this. Records are ideal for the state implementations.

import java.util.function.Supplier;

/**

* Represents a step in a trampolined computation.

* It can either be Done (holding the final result) or More (holding a thunk

* for the next computation step).

* This is a sealed interface, meaning only the permitted classes (Done, More)

* can implement it directly.

*

* @param <T> The type of the final result.

*/

public sealed interface Trampoline<T> permits Done, More {

/**

* Executes the trampolined computation iteratively.

* It starts with an initial thunk (Supplier) and repeatedly executes

* the next step until a 'Done' state is reached.

*

* @param <T> The type of the result.

* @param initialThunk A Supplier providing the very first Trampoline step.

* @return The final computed result.

*/

static <T> T run(Supplier<Trampoline<T>> initialThunk) {

Trampoline<T> currentStep = initialThunk.get();

while (true) { // Loop indefinitely until Done

switch (currentStep) {

case Done<T> done -> {

return done.result(); // Return final result

}

case More<T> more -> currentStep = more.nextStep().get(); // Compute next step

}

}

}

}

/**

* Represents the finished state of a trampolined computation, holding the result.

*

* @param <T> The type of the result.

* @param result The final computed value.

*/

record Done<T>(T result) implements Trampoline<T> {}

/**

* Represents an intermediate state of a trampolined computation.

* It holds a "thunk" (a Supplier) that, when executed, will produce the next Trampoline state.

* Implemented as a Record.

*

* @param <T> The type of the final result the computation will eventually produce.

* @param nextStep A Supplier (thunk) that computes the next Trampoline step (More or Done).

*/

record More<T>(Supplier<Trampoline<T>> nextStep) implements Trampoline<T> {}

We can rewrite factorial using our trampoline structure. We need a helper function that returns Trampoline<BigInteger> instead of calling itself directly.

import java.math.BigInteger;

public class FactorialTrampoline {

// Recursive helper: Returns either Done(result) or More(thunk_for_next_step)

private static Trampoline<BigInteger> factorialStep(int n, BigInteger accumulator) {

if (n <= 1) {

return new Done<>(accumulator); // Base case: Computation finished

} else {

// Recursive step: Return a THUNK that computes the next step

// The lambda () -> ... IS the thunk (a Supplier)

return new More<>(() -> factorialStep(n - 1, accumulator.multiply(BigInteger.valueOf(n))));

}

}

// Public entry point

public static BigInteger factorial(int n) {

System.out.println("Starting factorial computation for " + n);

if (n < 0) {

throw new IllegalArgumentException("Factorial not defined for negative numbers.");

}

// Run the trampoline loop with the initial thunk that starts the process with n and accumulator=1

return Trampoline.run(() -> factorialStep(n, BigInteger.ONE));

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

System.out.println("Running Factorial Calculation...");

int smallN = 5;

BigInteger smallFactorial = factorial(smallN);

System.out.println("\nFactorial(" + smallN + ") = " + smallFactorial); // Expected: 120

System.out.println("\n---------------------------\n");

// Test with a larger number that *would* cause StackOverflowError with direct recursion

int largeN = 20000; // Adjust based on typical default stack size limits

System.out.println("Running Factorial Calculation for large N (expect many steps)...");

try {

BigInteger largeFactorial = factorial(largeN);

System.out.println("\nFactorial(" + largeN + ") computed successfully (result is huge!)");

System.out.println(largeFactorial); // Result is very large

} catch (StackOverflowError e) {

System.err.println("\nERROR: Unexpected StackOverflowError! Trampoline failed?");

} catch (Exception e) {

System.err.println("\nERROR: An exception occurred: " + e);

}

}

}

Heap vs. Stack

The crucial difference is where the work happens.

- Standard Recursion: Each call adds a frame to the

Stack. Deep recursion -> Stack Overflow. - Trampoline Pattern:

- The

Moreobjects and the Supplier lambdas (thunks) they contain are created on the Heap. - The

runmethod’s loop executes within a single stack frame. Callingsupplier.get()executes the next piece of logic, but when that piece returns itsMoreorDoneobject, execution returns to the run loop’s single stack frame. - The “call chain” is broken into heap objects processed iteratively by the loop. The stack doesn’t grow deeper with each “recursive” step.

- The

Summary

In this post, we explored how Thunks and the Trampoline pattern can be used in Java to transform deep recursion into safe, heap-based iteration. We investigated the limitations of traditional recursion in Java, especially the dreaded StackOverflowError, and explained how functional programming techniques like Tail Call Optimization (TCO) in Scala and Trampolining in Java provide elegant, stack-safe alternatives.